By Mantoe Phakathi

Scientists are working with different stakeholders in four African countries to produce a framework that will inform agriculture and food systems policies.

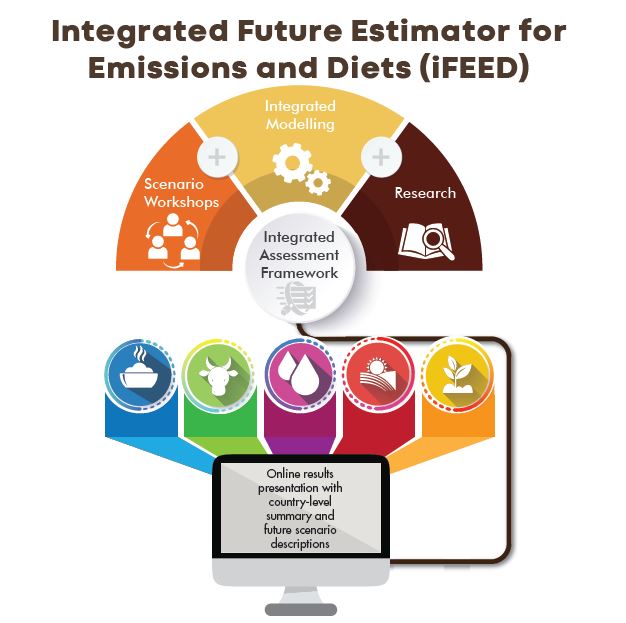

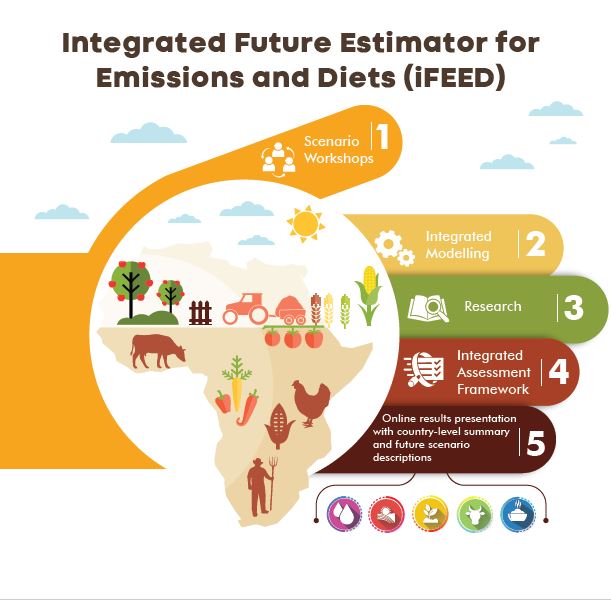

The integrated Future Estimator for Emissions and Diets (iFEED) framework will result in a portal with information on how agriculture and food systems will look in Malawi, South Africa, Tanzania and Zambia in 2050.

According to Dr. Stewart Jennings, a postdoctoral researcher from the University of Leeds, iFEED comprises outputs from climate change impacts and emissions models produced in collaboration with different experts in the four countries. This framework aims to indicate how food production will look in 2050 and how nutrition security can be achieved. The iFEED framework also seeks to determine the future of land-use patterns and emissions associated with them in 2050.

“We’re not only thinking about how a few crops are going to perform with climate change – we’re also thinking about how diets could look in the future,” said Jennings.

The evidence produced from the iFEED process is important because the United Nations projected that Africa’s population will double by 2050, from 1 billion to nearly 2.4 billion. In the meantime, the Inter-governmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has warned of severe climate-related impacts such as droughts and floods, which will further reduce food production, if global warming rises to 1.5° above pre-industrial temperatures.

iFEED is the result of work done under the Global Challenges Research Fund – Agricultural and Food Systems Resilience: Increasing Capacity & Advising Policy (GCRF-AFRICAP) programme led by the University of Leeds and the Food Agriculture and Natural Policy Analysis Network (FANRPAN). The iFEED framework is one of the main AFRICAP outcomes and involves collaborative efforts by all partners, including UK-based organisations (Met Office, University of Aberdeen and Chatham House) and African organisations (ESRF, Tanzania; CISANET, Malawi; ACF, Zambia; NAMC, South Africa).

The main objective of iFEED is to provide a basis for evidence that will help policymakers to produce policies that will consider future scenarios in agriculture and food systems, said FANRPAN CEO, Dr Tshilidzi Madzivhandila.

“The iFEED outputs are providing insights from different policy scenarios that national policy processes can use for decision making particularly those related to, for example, the National Resilience Strategy, the National Agriculture Policy, and Climate Change Policy,” he said.

According to Jennings, by mid-2021, the iFEED process will be on the last phase of combining the expertise of other academics and country stakeholders to summarise the results.

“To expand upon model results, we need to bring in other experts to explore implications of the results which the models cannot directly speak to – for example, thinking about whether there are any socio-economic barriers to the changes the modelling proposes,” said Jennings.

The iFEED process started with stakeholder participatory workshops to develop different future scenarios under modelling in the four countries in 2018.

The framework is a way of combining modelling with expert judgement to help inform agricultural policies, said Professor Andrew Challinor, from the University of Leeds.

“If we rely only on models and what models can do, we wouldn’t be able to say a lot about the nutrition outcomes or trade,” said Challinor, adding: “For example, we don’t have a model for pests and diseases, but we do have two people who have expertise in that area who can look into the scenarios and make comments about the challenges and opportunities under these different scenarios.”

The iFEED framework is expected to be in place in December 2021. Although it is directed at policymakers, some of the information will be available to members of the public who sign up to the portal.